In yoga-vinyāsa, the movements are led by the breath. This is the original style of yoga practice that integrates the prānāyāma stage into the āsana practice, helping the yogin to merge the āsana stage with the prānāyāma. The order that unfolds into a coordinated series is called the krama. This sequence contains the intermediate steps of āsana postures as defining the vinyāsa of the principal āsana. Herein one can think of vinyāsa as literally “one movement into the next” while krama implies “placed in a certain order.” Those intermediate steps are also individual āsana but linked with pauses in the breath to structure the flow into a complete sequence of the principal āsana to which the whole vinyāsa is ascribed. Hence an appropriate name for this style or approach to ashtānga–yoga (widely acclaimed eight-limbed yoga of sage Patanjali) is yoga-vinyāsa-krama.

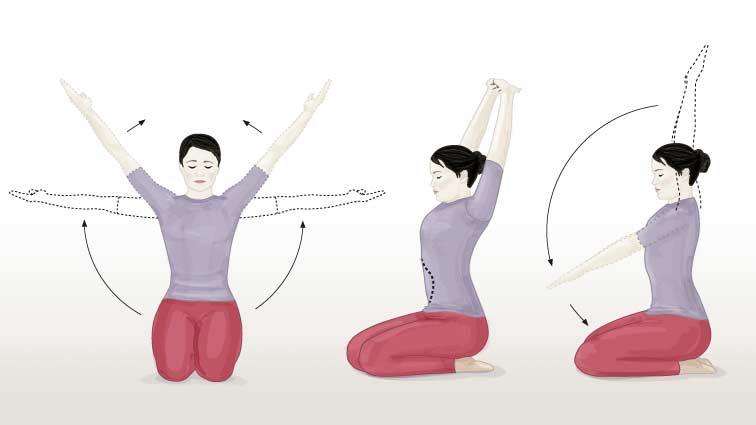

One should use the invigorating ujjāyi breath during this practice. The flowing movements linking the intermediate postures are superimposed on the ujjāyi breath. Thus, the coordinated movements linking the intermediate postures are synchronized with the breathwork. Therefore, the hallmark of yoga-vinyāsa-krama is the harmonizing of movements with the breath. Each separate movement is usually associated with an inhalation or exhalation (typically depicted by upward and downward arrows respectively in pictorial guides). Once the practice matures and initial experience has been gained, one may hold the vinyāsa or the āsana for a specified repetition of breaths using long smooth ujjāyi inhalations and exhalations.

The poise and grace of linked yoga-vinyāsa movements is like a slowly choreographed dance. Well-performed yoga-vinyāsa-krama clearly shows why it can be deemed as a precursor to classical forms of dance. Keen observers of this tradition promptly relate it with certain qualities of classical Indian dance. The higher the quality of the prolonged ujjāyi breath, the more deliberate and enriching the movements become. The breath is typically held (kumbhaka) or paused in between inhaling and exhaling. While great control may be needed, the movements should also flow gracefully into one another. In the Himalayan tradition hailing from select mountain lineages, the movements are swanlike, graceful and delightful to watch.

While practising the basic techniques of yoga-vinyāsa-krama, the breath will rarely become laboured and the pulse rate will not race. Aerobic exercises have their place in building fitness and strengthening the cardiovascular system, but this form of yoga is designed to bring down the breathing rate and reduce the heart rate thus increasing sāttwika tendencies such as calmness. This is what makes yoga-vinyāsa-krama an ideal preparation for the fifth stage of pratyāhāra (natural subjugated state of the sense organs) in the eight-limbed yoga of the sage Patanjali Rishi. A guideline for the duration of ujjāyi is 6 seconds as a beginner breath and 12 seconds as a good quality breath. A slow and smooth ujjāyi of 18 seconds while moving the body as per the vinyāsa is considered a masterful breath. Exhalation and inhalation always ends when the posture is achieved at the end of the transition and all movements cease momentarily. The next movement resumes with the breath again thereafter.

Each vinyāsa sequence works on specific groups of muscles and joints. The order of the sequences is carefully designed into a powerful cycle, strengthening the muscles and providing optimum flexion. An important point of this yoga philosophy is how the prāna from the synchronized ujjāyi breathwork is directed into the cartilage tissue during the movements. Specific nādi are targeted during the workout in each krama with the aim of directing the prāna into cartilages for rejuvenation. The flexion of the spine is given special importance in relation to how the torso and extremities get a workout. In this practice, the counterpose (pratikriyā) is deemed extremely important so that the effects on certain parts of the body including the directional spinal flexions are effectively balanced or neutralized. The krama itself includes such counterbalancing poses and built-in transitions, and by no means can these counterposes be skipped or marginalized.

Yoga philosophy also emphasizes the importance of healthy knees for successful practice of the three higher stages of āshtānga-yoga namely, attention (dhāranā), meditation (dhyāna) and absorption (samādhi), the triad of concentration deemed very relevant to an aspiring meditator. Seated poses and their vinyāsa are considered important for prānāyāma and meditation (collectively the highest three limbs of ashtānga-yoga). However, the standing pose vinyāsa are deemed primary and fundamental to the growth of the practice into seated āsana-siddhi (perfection of āsana for meditation). Virtually all major muscles and joints are taken up to be worked upon in Tāĺāsana. The krama related to this particular group of standing vinyāsa varies based on the root tradition, but by and large bears the same emphasis and employs the same thesis. This beginning sequence is considered to be versatile because several sub-sequences are embedded in it. The fundamentals of compact mini-sequences are also laid out and taught from this cycle, which then helps the practitioner develop a deeper understanding of the value of vinyāsa–krama. Even the popular Surya-namaskarah or sun-salutation cycle is deemed to be an invaluable extension of this Tāĺāsana vinyāsa cycle. All of this is launched from the root posture of samasthiti or standing on your feet with balance and inward focus.

A posture from which the actual sequence starts can be called the hub pose. However, in the classical tradition of this practice, almost all poses lead off from the standing samasthiti. The balancing required for this standing equipoise of samasthiti has a way of centring and quietening the mind. The samasthiti begins by standing steady and balanced with your two feet together applying equal weight or pressure upon the feet. Then you start guiding the ujjāyi exhalation and lower the hands by the side of the flanks. The subsequent basic steps in a Tāĺāsana series are built around raising the arms over the head with hands intertwined and palms facing upward. This is done in conjunction with an inhalation, and then the arms are released down to the sides with an exhalation. This movement stretches the diaphragm clearing out the lungs, massaging the heart and is deemed good for the lymphatic drainage.

An ardent practitioner of this system will recognize the impact on the cartilages and the spinal discs. In the classical tradition of yoga-vinyāsa-krama, cartilage tissue is considered an evolutionary checkpoint in our physical development, and hence deemed to play a critical role in removing physical disturbances hindering a steady meditation practice. While yoga-nidrā practice brings about quality relaxation by removing emotional disturbances, it is the practice of yoga-vinyāsa that is said to be ideal in removing physical disturbances. The way prāna is guided in the nādi and how the cartilages are replenished in vinyāsa-krama is a master technique that can be learnt properly under the direct guidance of an adept. The emotional disturbances and physical disturbances are deemed as fundamental obstructions in the path of yoga, and this is why the five restraints (yama) and five observances (niyama) have been structured as the Ten Commandments for the first two stages of the eight limbs of yoga. These ten vows then make way for the yoga-nidrā and yoga-vinyāsa related to the next two stages of āsana and prānāyāma of ashtānga-yoga (eight-limbed yoga).

Rigourous vinyāsa-krama can be done at a pace that suits the individual because doing too much or breathing too fast can produce giddiness. Certain sequences demand flexibility and strength in the knees and joints if they are to be achieved with ease and elegance. Careful and patient practice remarkably improves strength in these very key areas and parts of the body. Locks are often used to improve the balance, which is then very helpful when doing vinyāsa of the inverted postures. Fundamental to the success of this practice is the degree to which the mind guides the breath during the movement. Once the sequences are mastered and memorized, the movements will seem to be simply superimposed on the breathwork. Hence the mind is said to be minutely guiding the ujjāyi breath without any interruption. It is only then vinyāsa-krama is said to show results.

How basic alignment of the entire physique is treated, while stretching the muscles and energizing the joints during the flexional movements with guided breath, is an exquisite facet of yoga as an art expression. As again with such graceful movements, it is a good practice to rest in between the vinyāsa sequences. This can be in the form of extended pauses separate from the breath-hold pause during the vinyāsa. Of course at the end of a full session of vinyāsa-krama, it is highly advisable to rest in savāsana or the corpse pose for several minutes. This then closes the loop by leading into the practice of yoga-nidrā.

If you are interested in learning the Himalayan system of vinyāsa-krama we recommend that you attend a retreat, workshop or class by Self Enquiry Life Fellowship. Visit our events calendar to learn more.